I am more than a little surprised by the lack of attention given to the fundamentals of actuarial analysis and complex care management in discussions of ACO management. I see repetitive references to the criticality of deep data analytics, and to implement “data driven” decision making. But let me make a couple of somewhat obvious observations:

- It is likely true that the only way to make long-term real margin in the business of population health management, the provider organization needs to be at full risk for the management of patient costs (this is why health plans predictably make money). A particular physician group can certainly nibble around the edges of cost by managing referrals, attempting to influence ED utilization and being careful with prescribing, but this does not mitigate the risk of an outlier.

- If a provider group is actually going to take on full risk (not merely “risk,” but full risk) for a patient population, the population would need to be actuarially sound. The average MSSP ACO is less than 20,000 patients. MSSP patients are not even really “members” yet (since the patients may not know they are in an ACO), but that is a future possibility. Nevertheless, even if they were members, 20,000 patients are not remotely actuarially sound. “Sound” in this context means that the total costs of a population are credibly projectible into the future, within an acceptable margin.

- The top 1% of patients average costs of about $200,000 per year. If a group of 20 primary care physicians are managing 20,000 patients get and “extra” three of those top 1% patients, that is an incremental $600,000 reduction in their base pay. That looks like $30,000 per physician to me. If they get an extra 6 of the top 1% (again, out of 20,000 patients) they lose $60,000 each. That would be about 20% of the average primary care physician’s compensation. Ouch.

- I guess those physicians are not buying expensive groceries that year.

- …Unless the group buys reinsurance (more about that below).

Further,

- It is NOT usually difficult for physicians to identify the patients who are at risk for becoming outliers. Most primary care physicians can identify their top 10 risky patients off of the top of their heads. The question is NOT who is at risk. The question is what to DO about the risk.

- Most physician organizations are not large enough to deploy care management resources (e.g., complex case managers, in-home clinicians, clinical call centers, etc.) to mitigate the risks of their complex patients.

- They do not need more information about their patients. They need more resources to care for the outliers. It is not that deeper analytics are not useful. The issue is that deep data analytics are not the largest need.

Reinsurance?

The dearth of discussion about reinsurance in the context of managing risk in patient populations is more than a little surprising. Large reinsurers manage the risk that cannot be handled by parties at risk for a small population. Many small health plans (100,000 to 300,000 members) buy reinsurance to mitigate the risk of an unexpected debacle in any one year. Reinsurers aggregate risk for a number of small populations and manage the risk of a larger population. The size of the reinsurance premium is based on the degree of risk passed off to the reinsurer. There are several models for the reinsurance framework, but for now that is below the noise.

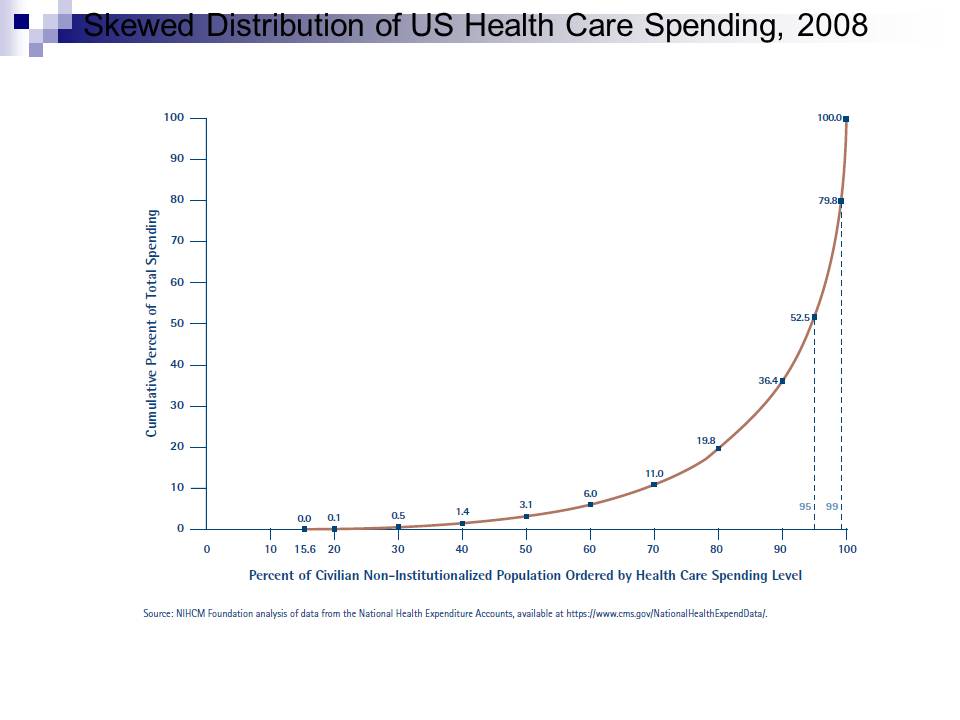

The problem for providers (and reinsurers) is that a very small number of patients consume most of the costs. The top 2% of patients are about 32% of all costs in the US. The average cost of a patient in the tops 1% is about $200,000. The next percentile down is about $120,000. These two brackets are the majority of manageable costs in the population. If a physician group buys reinsurance for patients that cost more than $100,000 per patient (for example) they will likely have successfully mitigated the risk of being unable to afford groceries the following year, but they have also obliterated most opportunities for cost savings. Further, a physician group, unless very large, would not likely have resources to deploy non-physician clinicians in such a way to manage the risks of these high-risk patients. What are physicians to do?

Health Systems Could Step Into This Breach

Let’s assume (for the sake of argument) that the minimum patient population that be actuarially sound is 200,000 members. (I do understand that commercial populations could be smaller, and Medicare populations could be bigger, but let’s finesse that for the moment). “Actuarially sound” in this context means:

- The costs are credibly predictable within an “insurable” band, and

- The acquisition of reinsurance can be set at such a point that the attachment points for reinsurance do not obliterate any opportunities for savings.

What is the structure that a health system could deploy to assist primary care physicians with their risk-bearing populations? There are four key steps in the process:

- Aggregate risk-bearing populations- The health system should act as the intermediary reinsurer (yes, this requires an insurance license and some new skills). Health systems can acquire a reinsurance license and charge risk-bearing groups insurance fees for their respective populations. The health system could offer internal reinsurance to ten or more 20,000-member risk-bearing populations. The health system would then buy reinsurance at a much higher attachment point (think $300,000) than could be afforded by the primary care groups, since the health system is now managing a 200,000+ member risk-bearing population. The health system would then use the reinsurance fees from the various risk-bearing primary care groups to subsidize key centralized care management resources. The health system in now in a position to directly contract for incremental risk-bearing populations as well.

- Deploy centralized care management resources- The health system should deploy common resources to support the members that are explicitly in risk-bearing populations. The centralized resources would likely include:

- A clinical call center– The call center would be staffed by clinicians with access to patient EMRs. The primary objective is to be an immediate care resource for high-risk patients.

- A complex case management team– This team would have senior care management resources (typically senior care management nursing staff) managing a pyramid of less senior clinical staff (social workers, home aides, etc.) and specialty clinical resources (e.g., clinical pharmacists) all under the direction of a senior medical officer.

- Services to mitigate ED over-utilization– This is highly geography specific, but might include 24 hour primary care offices to handle non-emergent overuse of ED resources by risk-bearing population members.

- Train the physician groups to integrate care with the centralized resources- This includes not only definition of care coordination processes between primary care and the centralized care management resources. It also includes aligning incentives such that the groups that are effective in mitigating care costs would experience a reduction in internal reinsurance costs the following year.

- Improve, improve, improve- Any of you that have attempted any of this know that this is actually really difficult. But this is likely the only viable path to effective management of care costs for the majority of US primary care physicians. The rare physician groups that are at risk for over 200,000 to 300,000 patients have some other options, but we can take those as a special case for the moment.

The objective in this effort is for all parties to work together to get the costs of reinsurance down (both for the individual physician groups and for the health system). Herein likes the majority of margin in the model. Once a health system is effective in complex care management, the health system can transition to a greater fraction of total patient volume at full risk. Full risk directly translates into a higher per-member-per-month reimbursement rate from the payers.

Summary

My suggestion is that deep, complex data analytics are useful, but fundamentally secondary to deploying the centralized care resources necessary to mitigate the risks of outliers within patient populations.

I look forward to your comments (and, hopefully, arguments).

You can see that the graph shows the top 1% consume about 20.2% of care costs, and the top 5% consume about 47.5%. I think (but I am not sure) this is the overall US healthcare population (it sounds close).

You can see that the graph shows the top 1% consume about 20.2% of care costs, and the top 5% consume about 47.5%. I think (but I am not sure) this is the overall US healthcare population (it sounds close).